With their words and images, our 2021 creative writing and art competition winners answered the question: How does migration shape life in your community?

View the submissions of our six winners.

Table of Contents

On Borders: Life, Deportations, and Mobilities along the Haitian-Dominican Border

Karina Edouard, Graduate Student in Anthropology

These photos were taken in the border town of Anse-à-Pitre, Haiti in 2017. At the time, I was working for the International Organization for Migration where I conducted research and collected data on the illegal deportation of stateless Dominicans of Haitian descent by the Dominican government. I spent a great deal of my time at various official border crossing points between Haiti and the Dominican Republic and witnessed the complexity of life at the border. There were innumerable deportations, as well as food stands, vendors, and transportation services. The Haitian-Dominican border reflects a space where tragedy and ingenuity, protest and resilience, and pain and joy seemingly converge. It is a space where mobilities are exercised both voluntarily and involuntarily, and where the Haitian state, the Dominican state, and the international aid community meet. Given this complexity, there can be no singular representation of the Haitian-Dominican borderlands. As such, I have selected seven photos I took during my time along the border that begin to give voice to this dynamism.

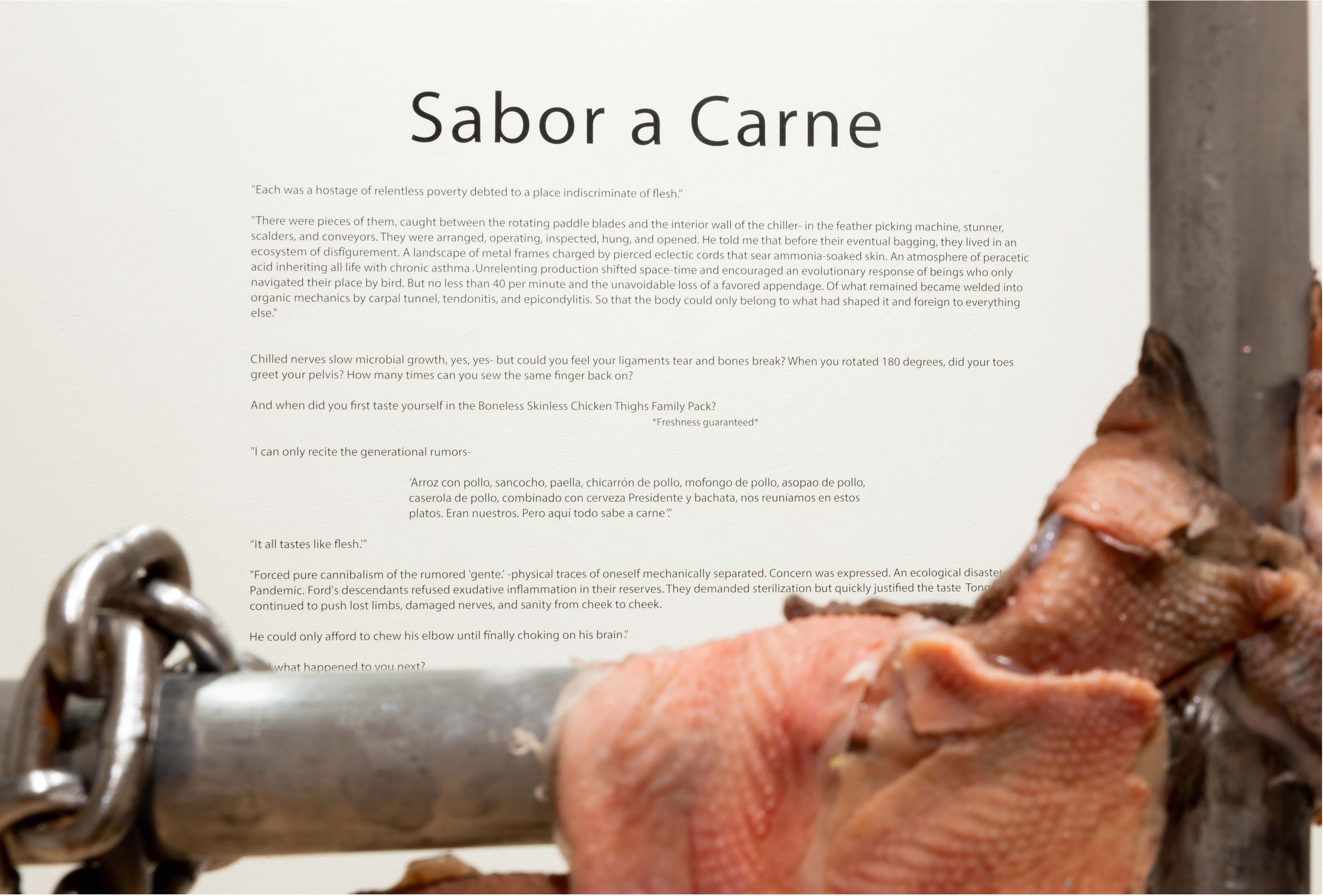

Sabor a Carne

Sabrina Haertig-Gonzalez '22, Fine Arts

"And when did you first taste yourself in the Boneless Skinless Chicken Thighs Family Pack? *Freshness guaranteed*."

Sabor a Carne is a sculpture series navigating the relationship of Latinx identity to poultry processing in the United States.

These works represent dedicated, intensive research of how the Latinx body is taxed through forced migration, dangerous labor, and the consumption of American chicken. At the intersection of exploitative policy and culture, one can observe a phenomenon of cannibalism. Chicken, or pollo, an inseparable staple to Latinx cuisine for most, is also inseparable from the unethical modes at which it is farmed and processed in mass- which heavily exploit the Latinx community. The exploitation of migrant labor and systematic disenfranchisement of the Latinx community lead many to work in dangerous employment such as meat processing, which compounded with the economic accessibility and cultural relevancy of chicken, positions them as products, producers, and consumers.

As one assumes these roles, what becomes of the “self?” What becomes of their relationship to the corporeal? Do corporeal bodies blur as violence is imparted by the human and non-human? This discourse is presented to the audience through the surreal manipulation of the corporeal and industrial. From adopting pre-Columbian aesthetics to designing imagined future architectures, Sabor a Carne posits when meat became flesh.

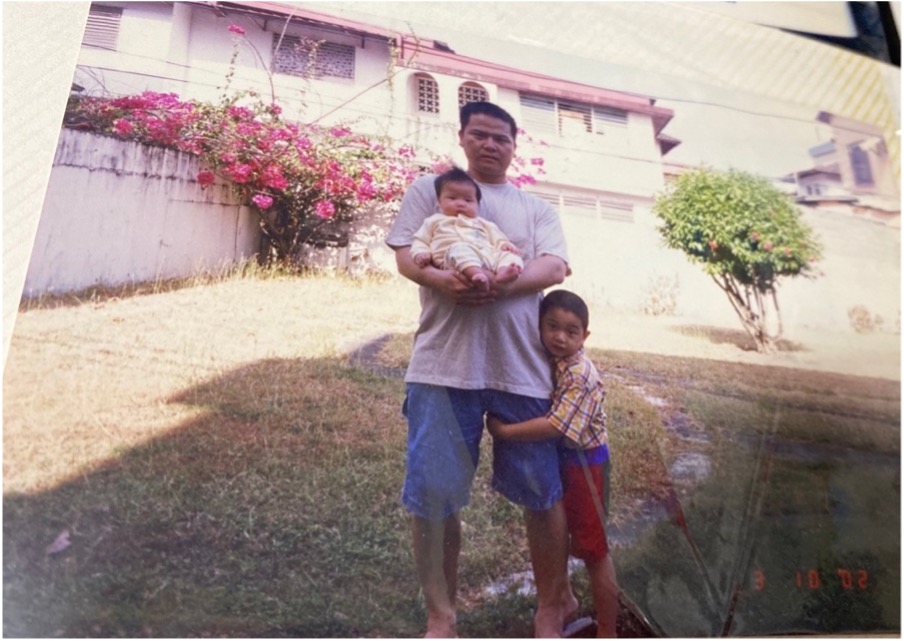

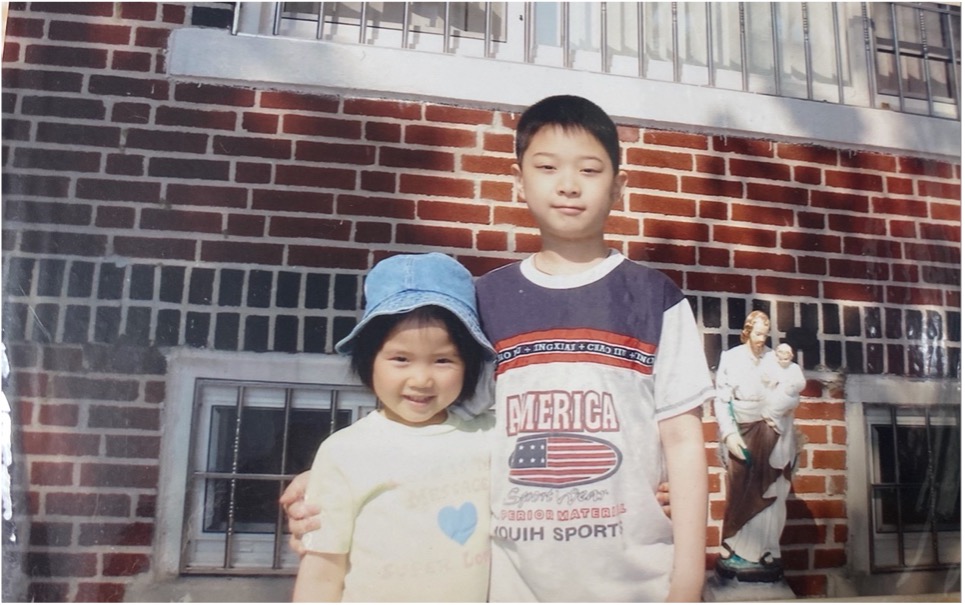

The History of Those Before Me

Michelle Cheung-Zheng '23, Environment & Sustainability

The education of the world beyond the urban landscape that raised me has been defined by the realities of the people and histories that brought me to my current community. In the re-education of my diaspora and family’s migration, "returning" became a concept that reconnected me to generations of land, families, and complex social networks. My perception of my family’s migration stories is weaved and shaped by the dispossession of identity, land, history, language, and culture.

My curiosity with my family’s migration history stems from the psychological dissonance between my identity and the cultural environment I grew up in. In New York City, where 11.8 percent of people identity as Asian American, internalizing experiences of discrimination and stereotypes became a subconscious reaction to processing my self-identity. Reconciling the dual identities that I felt as an Asian American woman meant that I had to understand more than my own upbringing; I had to understand the generational migration that happened within my family and how that impacted their relationships with the idea of home and what home represents.

The first migration story of my family I learned, entailing the weight of generational adaptation, starts in southern China. My father comes from a family of eight, the only son out of six children. Migration came out of necessity and a need for financial survival. Disinheriting land and property became an unspoken agreement, a necessary process that moved my father to a new country. Conversations of this dispossession revived when I went back to that house in 2018. Standing in its now empty layout, I imagined stories of his family, their home, and their departure from it.

About one generation ago, my father and his siblings moved to Panama where they continued to live for multiple decades. However, a new migration story ensues after I was born. My father continued to live in Panama for a few years while my mom moved my older brother and I to our new home in Brooklyn. How do we grieve for the lives we would have lived and the people we would have become? To reconcile this is to first acknowledge that my self-identity has been context-dependent on my family’s migration history.

The migration stories above only cover what has been disclosed to me and within the bounds of my immediate family. However, migration within the rest of my extended family represent stories of their own and will become networked into their own families. Different family members have chosen to stay in China, Panama, and the U.S. Some have migrated to other places. Migration chains and effects are extensive and represent different needs, geographically and culturally.

In some ways, I have repossessed pieces of identity through navigating my family’s history of migration. Each generation of my family is linked by the resilience of self-preservation in the environments that built our identities and lives in China, Panama, and the U.S. Cultural and social ecosystems are integral to how our identities become tied to land. Preserving my heritage means to preserve my relationship with developing my own concept of home, merging multiple environmental perspectives together.

I have many more questions about the emotional and psychological impact of migration on my family’s individual identities. However, understanding that migration is not a linear story and that many stories get lost, either in translation or intentionally left out, has impacted how I continue to access these stories from my family. Reconceiving notions of identity throughout generational migration is a continual process, one that requires mental acceptance to truly reconcile how migration changes your family’s history and ultimately, your own history.

Meridian Root

Nicholas French '23, Human Ecology

The scent of asphalt simmered through my nostrils as we stepped out of the AMC theater. The image of neon from the Algiers Hotel and gun smoke were burned into my skull. I could see my grandmother materialize, piece by piece, as my eyes acclimated to the bright summer sun. First the wispy curls of her hair. Then her skin. Finally, her eyes appeared. They were pensive, quietly shifting—caught in a current of memory. She was actively analyzing what we had both just witnessed, forming a solid critique with memory as her guide. I wanted to hear her thoughts. She became a link between the present and past.

"So what did you think about the movie, Grandma?" I asked.

Beneath her eyes formed a smile, a tentative smile suggesting satisfaction and the slightest hint of distaste.

"They did a good job, but they got a couple of things wrong," she replied. "Everyone burned down buildings in those riots. Not just Blacks."

My grandmother’s arrival to the North was not unlike the tales of many mid-century African American families migrating to northern cities.

To some, the migration north was a pursuit of economic opportunity—a movement from the Bible Belt to the Rust Belt. The automobile industry served as a catalyst for a growing midwestern middle class. To others, the move north embodied an escape from the terrorism of southern racism—an arrival to a new personal Canaan as segregation and violence still ran rampant in the South.

My grandmother’s migration north was motivated by many of these factors. However, above all, it was for the pursuit of a better life, for both herself and her new family. Her arrival was different from other migrants in one particular way—she came to Detroit during the aftermath of the 1967 Detroit race riots.

Mary Powell Wright began her life in Meridian, Mississippi. Though her family was not rich, they had what she fondly recounts as "a good life." Her father—my great-grandfather—was self-employed and one of the best auto mechanics from Alabama to the Georgia line. Car owners, both Black and White, brought their cars to his garage for repair. Their home was a haven of renewal, both for cars and their neighbors. My grandmother’s youth was dictated by the unspoken creed of Mississippi: "Feed your community, and the community will feed you." Whenever dinner was made, there was always extra for neighbors and whoever needed it. Yes, she was living the good life.

In college, she met a young man that she grew to love and, in the future, marry. However, the couple knew that they wanted to move North. The two made their decision to move in 1967. Equipped with a loving relationship and a desire for opportunity, the couple made their way to Detroit, MI.

With incredible luck, my grandma did not arrive to burning buildings and gunshots tearing through the skies. She caught the tail end of the uprising, witnessing the carnage only through the echoes of gunfire and the smoke of businesses reduced to ashes. To my grandmother, the rebellion was not a blaze of fire, but the sickening warmth of cinders and police posted in the distance. She witnessed what happened both through her eyes and the headlines of newspapers, frantically explaining what had occurred. A single false gunshot from the Algiers Hotel coupled with decades of systemic oppression created a whirlwind of rage and fury, burning much of the city to the ground. It was believed that many white storeowners burned down their own properties and were reimbursed through insurance. To them, the flames presented an opportunity to move their business out of a city growing more Black by the year. The flames and tanks threatened to consume the lives of the Black migrants. However, if there is one thing that they knew best, it was how to root themselves into the ground and sprout community—even if the soil was charred. She earned her degree in education and raised a beautiful family.

After living on Garland Street near the east side of the city, my grandmother relocated to the Black and Jewish neighborhood on Pinehurst Street, closer to the west side. As time passed, the neighborhood grew more homogenous as white flight and suburbanization further segregated the city. It was here that my mother, aunt, and uncle spent their childhoods, and would eventually create my generation. When her children came of age and went to college, she moved to the suburban city of Southfield, MI. There, I would spend much of my childhood alongside grandchildren of countless other southern migrants.

Southfield is a city of many identities. A city of rolling hills and tall weeping willows, populating the streets with the staccato chirps of cardinals and grasshoppers. This natural melody scored my childhood adventures, bolstering my courage as I first learned how to climb the massive tree in my grandmother’s front yard and jump on a trampoline without breaking my spine. It is also a city of communal empowerment—a trait inherited from the culture of the South. Each Sunday morning an exodus of cars could be seen flying from the neighborhood at 9:40 a.m. (on the dot), just in time for Hope United Methodist Church’s 10:00 service. Most of all, however, it is a city of hope and sacrifice. The sacrifice of comfort for future opportunity. The sacrifice of familiarity for family. The sacrifices that enabled me to live the life that I live today. My history is entwined with my grandmother’s—rooted in Mississippi culture, faith, and perseverance. Despite the uncertainty, smoke, and cinders—we are here. Migration is my story.

Listen to French's interview with his grandmother.

Lupita's Shoes

Amalia Schneider '24, Industrial and Labor Relations

Guadalupe’s day begins every morning at 6 a.m. She sits up slowly and stretches because her muscles are still sore from the day before. When she stands up wearily and makes her way over to the bathroom to say her prayers in the mirror.

When she was a girl her mother used to brush her hair and recite them with her. She continued this practice with her daughters, Sarah y Graciela, back when they all were still together in México. Without them there, ella le pide a Dios que reúna a su familia every morning while she got ready for work. She steps out at 8 o’clock to walk three blocks to catch the subway. The El train arrives 5 minutes late and floods with people as it rolls in at 8:32. Whenever she rides the busy train in the morning, she liked to observe the "strange people"—or strangers, as her English teacher had called them. This morning, she sat across from a mother with her young daughter having a conversation about "crayons" she doesn’t understand, but she writes the word in her little blue notebook to look it up. Once she reaches 69th street station, she is so anxious about being late she races to her next bus which doesn’t arrive until 8:55. When the bus finally stops outside the Apple store in "Suburban Square" she is clutching her android as it reads 9:15.

But, she quickly turns the corner and arrives.

"Besito."

From the sidewalk, you can already hear "El Beeper" by Oro Solido blasting out the walls. Manager Mike is already at the host stand typing on an iPad as she walks in.

"Damnnn chica, you're late again today? What are we gonna do with you?" Mike jabs sarcastically. She doesn’t understand, but she sees him start laughing so she does the same. She giggles awkwardly and says "I sorry" as she makes her way toward the kitchen.

She is so tired of laughing at Mike’s pinches jokes, especially since he hadn’t paid her for a single shift all week. Of course Carla the bartender is always there with a flower pinned in her hair and a full face of makeup at opening to greet Guadalupe.

"Hola, mi amor. ¿Cómo 'stas hoy?" she exchanges in her beautiful Venezuelan accent.

"Bien," she says as Carla blows her a kiss that she steals with her into the kitchen. She sets her purse under the metal rack of plates and ties on her apron that still smells of salsa from the day before. Hours go by as she squats at a 90-degree angle to lift the 3 foot, 8 pound black trays that carry the food.

Le duele el cuerpo.

She looks down at her tattered black shoes. The soles of her work shoes have become indented from the hours of intense lifting; it’s at the point where wearing them for more than an hour makes her hip and spine ache, but she can’t afford to think about buying a new pair until they pay her. After the fifth hour on her feet, she starts to feel dizzy and asks manager Mike if she can take her afternoon break. As the break room gradually fills with more of the servers for the night shift, the bilingual chatter soars until the 7 o’clock news silences the chatter. "These people are criminals, drug dealers, murderers, rapists," he says.

¿Criminal?

The word played in her head while brushing her hair that morning.

It made her question herself.

Was it criminal to want a better life? Criminal to cross an imaginary line when you have no other option? Or is it only criminal when you have brown skin and a thick accent?

"They're stealing American jobs!"

That one made a server LaLu burst out chuckling. "¡Aye you can keep your pinche jobs, orange man! Besides, ain’t nooo ICE gonna catch me," and he lightens the mood by jogging with high knees.

Amidst the laughter, I come in for the start of my shift with Guadalupe. She launches from her chair and hugs me. "¡Hola, cariña! ¿How are ju?" she asks me, grinning.

"I’m good," I smile back.

"I have uhh-a-soorpriseh for ju." She reaches in her purse and pulls out a plastic container with a slice of carrot cake.

"Aww, Guadalupe, What is this for?"

"¡It is for ju!"

"But why?"

"Because ju got accepted in de university and I..." She wrinkles her nose in thought and then closes her mouth tight. She squeezes my shoulder gently as if to signal what she had wanted to say got lost in translation.

"Thank you," I said. "We can share it."

"¿Sharar?" She looked confused.

"Compartir,” I translated, and she nodded and smiled.

This was the last time we were all together as a family at Besito before COVID scattered each of us back to our own corners of Philadelphia. IfI had known that was the last time I would see Guadalupe, I would’ve made sure that I never lost contact with the woman who had become my family through work. Even though she was 65 to my 17, I could do nothing but empathize with this kind woman who gave up everything in migrating—respect, family, stability—and worked nonstop to help those she loved in Mexico. Through Guadalupe especially, I watched all the ways this country makes immigrants feel invisible, yet burdensome at the same time.

So, while writing this story cannot undo all the injustice Guadalupe has received for something as human as migration, at least I can find some peace in knowing that she is no longer invisible here.

I write this to rebuke on her behalf the notion that immigrants deserve anything other than empathy. "Illegal" or not, immigrants are still people—people who shouldn’t have to beg and plead for understanding. Dios sabe que they’ve been through enough. So, I invite you to take a walk in Lupita’s shoes.

Water Diaries

Skylar Xu '24, Comparative Literature

When we first moved from home-town to big-town, grandma couldn’t get used to the water. She would filter the tap water using a row of large pitchers and jars, letting water sit before passing it to the next pitcher or jar. Grandma had lived most of her life in home-town. The water there was different, she said. Softer. You could feel it on your skin when you showered. The water was softer. What she means is that the water is less alkaline. Anyway, it was years before we got a water filter installed beneath our sink, so she filtered water with a row of pitchers and jars. I grew up drinking kettle-boiled water.

(Is there something in the water?)

There is a difference in taste between boiled tap water and bottled water. I know this because I grew up in a country where tap water was not potable. Boiled tap water has a cloudy, vague texture and usually doesn’t taste like anything. Bottled water, on the other hand, is sweet and bitter at the same time, leaving a dry sensation like the aftertaste of a too-green banana or that of an early persimmon on your tongue. I never got used to the taste of bottled water. I’ve lived most of my life in big-town. It’s called big-town because it’s bigger than home-town, and because it’s where people go if they want to make it big. Whenever we visit home-town, I try my best to gauge the softness of water like grandma had described. If I did feel it, chances are I imagined it or it was some sort of placebo effect. But I was born in home-town, and since it was where my parents and grandparents lived for most of their lives, I always wanted to feel like I came from home-town, too.

(Is there something in the water?)

People from home-town say I sound like I come from big-town, and people from big-town say I sound like I come from big-country when I speak the language. I have never heard anyone other than myself talk about the smells and tastes of water. Maybe I’m crazy. I might as well be, because now I’ve left big-town, more or less on account of my own will, if you can call it that. I’ve quit home-country for big-country. And here in big-country, they drink tap water.

(Is there something in the water?)

I was fifteen when I first came to big-country. I was fifteen, so I don’t think it was a decision based purely on my own will. I didn’t even know why it was called big-country, only that everyone else had called it that. When I first came, I couldn’t tell if the water was softer or harder, only that alkaline formed on the base of the electric kettle. When I was really young, water was boiled in a kettle that was not electric. It sat on top of the stove and whistled when the water was ready. A shrill but not unsettling whistle.When my parents were my age, they lived in home-town. They must have gotten a taste of big-town water one day, because all of a sudden soft home-town water wasn’t enough for them anymore. They had to move to big-town, as if there was something in the big-town water. I wonder if the same thing is in big-country water, too, because after a taste of it, home-country water wasn’t enough for me anymore.

(Is there something in the water?)

A water filter gets put under the sink back home, in big-town. The new filter is supposed to make tap water potable, but no one uses it. We’re used to drinking boiled water. Tap water, filtered and drinkable, still feels like tap water. I bet it’ll even still smell like tap water. Ever so slightly metallic and reminiscent of clean soil. Here in big-country, no one can tell that I’m from home-country by the way I talk. In fact, I don’t want anyone to tell that I am from home-country. When I speak in class, however, my voice tastes like tap water. Undrinkable, slightly metallic, reminiscent of soil. But this time it’s the kind of raw soil that dirties your hands, not the clean kind that nourishes gardens. I imagine myself taking on stutters, starchiness, and a raspy quality that my voice does not have. No one else hears them but me. Everyone else’s voices taste like bottled water. In home-country, tap water is becoming potable in some places. We have electric kettles now, and we only use the shrieking kettle when the power goes out. Big-town water still won’t be as soft as home-town water, though, and I know neither of them will really be the same as the water in big-country. Is there something in the water?