How does migration shape life in your community?

View the submissions of our six winners.

Table of Contents

Zungiera Mundial

Catia Dombaxe, Graduate Student in Chemistry and Biomedical Engineering

I was born in Luanda, Angola, in a culture where the philosophy of Ubuntu has such a deep personal meaning that it felt like this life philosophy was engraved in me from a young age. Growing up, I really did not understand individuality, because I was always part of the collective. I was part of everyone, and everyone was part of me… That is how I grew up and to this date I hold true to these beautiful roots. UBUNTU, one of my favorite life philosophies, will always define who I am and allow me to strive for and achieve ever-increasing challenges that I undertake.

The concept of Ubuntu has been developed by Desmond Tutu, but many Bantu tribes in Africa have lived by the principles since the early years. Ubuntu is a way of living; Ubuntu means I am who I am because of all of us. Ubuntu is part of the collectivism I spoke above. I live by it and I would highly advise you to adopt it and make it part of who you are. Ubuntu has shaped me and allowed me to grow because of the infinite support, life lessons, and a sense of belonging.

Ubuntu has allowed me to adapt in every environment I move into and make that my home as well. Ubuntu to me is migration, migration is zungueira mundial, and zungueira mundial is all of us.

Zungueira mundial is Portuguese. In Angola, a zungueira is a slang term for a peddler woman. It is a woman carrying a large plastic bowl of food and many other goods on her head, with a baby strapped to her back, trying to survive Angola’s difficult economic challenges. Zungueiras are very well known in Angola, due in part to their tenacity and willingness to do what it takes. They are known to walk great distances in order to sell their goods and make money to feed their children.

I associate with zungueiras because migration is survival for me. I, too, have walked great distances to get where I am, carrying the weight of the people and places I have met and explored, because I feel I carried the responsibility to connect them to you. For me, this is how I feed not only myself but also the world.

With these photographs, taken around the world during the different migrations of my life, I truly would like to entice you to look beyond visuals. I want you to feel it: every place, every face, every smile, please feel it! That is migration. I urge you to explore, get out there, meet people with different backgrounds, each and every one tells a story, learn something with them and something about yourself along the way.

Explore beyond your roots.

Creating Home

Ishika Agrawal '23, Information Science

The following set of poems are written from three different perspectives—a grandmother, a mother, and a daughter. It explores the intergenerational relationships that immigrants retain with their homeland and its histories pre-migration, just after migration, and a generation later.

I. The British Raj

seven letters weigh 89 years of dreams deferred

of don’t worry, I’ll walk

the 5 rupee bus pass costs too much

of here, this is how you chop

a knife, not a scalpel, fits a woman’s palms

of please, say your grievances

my 8-month-old brother was just killed by an officer with a rock

August 1947

after 89 years of ice

pots clang

hoisted at full mast

a flag torn into three parts

it’s time now -

to fulfill every deferred dream still hovering

the family tree path

do I have what it takes?

that matters not

it is a duty I carry

passed down to every child,

keeping our ancestors alive

with the same seven letter family name

II. Time Capsule

I massage almond oil into my hair

just as my mama did

sip my chai from a red clay cup

just as my papa did

choose a matching bindi every morning

just as my nani did

sing the Gaytri Mantra head bowed to Lord Ram

just as my dadu did

8000 miles away

I’ve created a piece of home

that smells like ground clove and rose agarbatti

sounds like the chattering of aunties as they knit woolen scarves, away from the monsoon rains

feels like the early morning excitement just before the whole neighborhood arrives to play Holi

but as I’ve built my home

scouring my memories

to put it together piece by piece

the world has changed

8000 miles back home

my niece prefers an organic rosemary hair serum

to my mama’s almond oil

my brother-in-law prefers a ceramic mug

to my papa’s red clay cup

my sister prefers the modern look

to my nani’s bindi

my nephew prefers Coldplay

to my dadu’s early morning aarti

the home I long for 8000 miles away

isn’t truly home anymore -

my people have changed

my culture is dissolving

my world has moved on

but in this time capsule called home

that I’ve built

I can pretend.

Nothing

has changed.

III. Home

I imagined home as the

four lemon sorbet walls tucked between sugarcane fields.

Before that, it was every story my grandmother

told. It was sitting on marble floors

gulping alphonso mangoes, juice running from the mouth. It was

the I miss and the I wish and the Grandma,

there are no mango trees here.

It was a desert mirage, blurred

by a post-Diwali firework haze -

a distant, foreign familiarity

conjured by my mother’s peculiar love

of peacock feathers and fennel seed paste.

Spray-painting my bottle-green bedroom

with Benjamin Moore’s can of lemon sorbet.

I declare I am home.

Who needs sugarcane fields when living

the white picket fence dream? Who needs

alphonso mangoes when there’s plenty of apple trees?

Boarding the New York subway, my two-year old sister

rests her hand on a gentleman’s knee.

He brushes her imprint off, as if

swatting a flea. My father warms my dinner

as I read in the hotel lobby when a concierge’s

What is that smell? febreezes the aroma of palak paneer.

I gulp an apple but the seeds get stuck in my throat -

a sore reminder of why mangoes have juice and

picket fences can’t contain sugarcane fields.

Reluctant Fundamentalists During Seasons of Migration to the North

Shehryar Qazi '24, Government

The title of this piece refers to two novels: Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist and Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North. If I had to describe what the book was about, I’d say it's about hybridity and being a colonized subject in the imperial core. But my readings of the texts are fundamentally colored by the similarities I share with the characters as a colored, foreign man attending one of the most prestigious institutions of higher learning in the West. All our lives are so fundamentally shaped by migrations: labor, educational, and political. So fundamentally, I can’t disentangle my reading from my life, and the texts become about who the migrant really is, who I “really” am, especially divorced from any sort of “native” context.

Both texts are incredibly packed and dense, so I will note that there is so much more to them than some of the things I talk about. Seasons of Migration to the North is a sort of “Arabian Nights in Reverse.” The story follows the life of one Mustafa Sa’eed, a brilliant economist from Sudan who studies at Cambridge and becomes a respected anti-colonial economist among the highest ranks of British society who returns to Sudan to start anew, through the lens of a narrator who is also British-educated Sudanese and becomes obsessed with Sae’ed. The Reluctant Fundamentalist is about Changiz, a Princeton-educated Pakistani investment banker and his reaction to 9/11, eventually returning to Pakistan because of the racism he faces after 9/11 and getting a job at a university criticizing American intervention in Pakistan.

These two texts raise a lot of ethical questions about complicity and about self-authorship, and I consider them in lieu of my social milieu. The third world aspiring upper class educated in the West, with hopes and dreams of achieving status as part of the international leisure class. I more so think of this when I think of my Pakistani friends who break into the top computer science and finance firms in America, and my heart aches to know that some of the sharpest and most brilliant minds from home are using their abilities to exploit the Global South, servicing some of the most crooked and evil institutions of the world. But many of them do not have Changiz’s realization in The Reluctant Fundamentalist that the actions they are doing make them foot soldiers in American Capital’s destructive war on the rest of the world. Instead of Reluctant Fundamentalists, they remain eager janissaries.

But then again, the life of the scholar represented by Mustafa Sa’eed is not without its ethical problems either. What does it really mean to produce knowledge about the place you’re from, especially in the context of the Western Academia? The conversation about the centrality of indigenous dispossession to the project of the American university system is slowly rising in volume, but has yet to seriously explode to the point where we acknowledge and do the reparatory work necessary to deal with this legacy of dispossession. But there’s more to this, as the American academy and production of knowledge is so influential in how we view the world. From the creation of the atom bomb at a squash court at the University of Chicago, to the printing of Mujahadeen textbooks at the University of Nebraska Press, the American academy has been deeply involved in the twentieth century’s most destructive developments. “Knowing” always has political implications and if you’re in the position as a foreigner to contribute to this system of “knowing,” then you probably represent a very select, usually upper-class, social and cognitive group. The figure of the metropolitan migrant is a limited one, yet it is the best we can seem to do in the American academy.

But this is not to be wholly critical of everything ever produced out of the American university. This essay is produced out of this system. Nor do I have answers to the ethical problems confronted by the figures of Changiz and Mustafa Sa’eed. I simply wish to raise them and see where they lead me into thinking about what sort of life I want to live.

My family history has migration built into it. My grandmother from my dad’s side was from Iran and moved to Ferozpur, now in Indian Punjab, to marry my grandfather who had been a judge in the city for generations. They then moved to Gujranwala, in now Pakistani Punjab, during Partition, and then moved to Lahore in the early 1950s. My grandfather and grandmother took a world trip during the early 1970s, their trip to New York being recorded on home video. My mother’s family moved from Sialkot to Lahore and is now scattered all across the world, from America to the UK to Russia to Saudi Arabia.

I myself always knew that I would spend significant time outside Pakistan, but am challenged by this time outside. I have not been “home” in five years, and have somehow found myself in Cornell's government department, having to sit through abstracted discussions of drone strikes, knowing what they were doing to people in Pakistan in the 2010s. Terrorism became a form of “asymmetric warfare” and suicide bombings as “insurgent weapons,” and not the reality of living or growing up in Pakistan during the War on Terror. I always felt a sort of disconnect between my life in Pakistan and my educational life in America.

I read the two texts as cautionary fables. Of course, no one will ever fully be a Changiz or a Mustafa Sa’eed, but these two figures are warnings of life in the West for the Global Southern metropolitan migrant. But these two texts also firmly deal with the question of return, which is presented as a bittersweet situation. Depending on how you read the stories, both Changiz and Mustafa meet unenviable ends. But I can only sigh at my disconnect from “home,” unsure of return. Maybe that is an unenviable end in and of itself.

The Migration of a Daughter to Immigrants

Fatima Martinez '24, Psychology

If I were to mention the date March 13, 2020, you, me, and almost the entire world would remember that date as the day the world stopped. COVID had forced us all to isolate, drop our daily routines, responsibilities, and take them home with us. But that day, in particular, I remember it as the day my world stopped but also started. Does that make sense? I know it sounds crazy. But it was the day I was getting ready to leave school for “two weeks” when I received an email. Not thinking much, I opened it and received a likely letter from Cornell University. Given how crazy the day had been going, I had to reread the letter five times before I actually understood what I was reading. And then I felt my heart drop to my stomach.

“Is this real?” I asked my younger brother as I showed him the email I received on my phone. The rest is a blur, but I remember him crying, shouting at my face with excitement, shaking my shoulders and saying, “You got in.”

When I told my parents that I got into Cornell, they didn’t really understand. The only thing they processed was that it was a school in New York. “Why do you want to go to school in New York? I came to Los Angeles because it has everything. And now you’re leaving it!” said my dad.

“She wants to leave us. She wants to leave me,” said my mom.

My family didn’t understand, only my 15-year-old brother did. He was the one who convinced me to apply to Cornell in the first place. Regardless, I let the subject of conversation go because part of me felt like my family was right. What if the likely letter was actually sent to me by someone who was trying to play some joke? What if this was all a lie?

“No vas a ir. Ya te dije,” yelled my mom.

“Why not? Can’t you see this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity?” I responded.

“You just want to leave me. And leave all of us. Is that what you want, to abandon us?”

"I never said that! Why would you even say that?”

“Then why do you want to go?”

“Because they’re a good school. They’re paying everything!”

“There’s no need to go so far, not in the middle of a pandemic! And you know that just because they're covering tuition doesn’t mean there aren't other costs. What about your plane tickets? Essentials?”

“I’ll figure it out. I’ve saved up enough money from my summer jobs.”

“If you leave, I’m not helping you. I’m not going to drop you off.”

“That’s fine. I promise I won’t ask you for anything.”

At the end of this conversation, I was in tears, snot was coming down my face. But I was determined to go, I had worked so hard for exactly this. Maybe not particularly aiming for Cornell, but for a good school—to make it out.

By the end of the summer, I had shipped two boxes across the country and only had my father’s blessing. “Es por tu bien, yo entiendo,” (it’s for your own good, I understand) he said. “Yo también hice lo mismo, solo que yo no migre solo. Yo vine a este país con tu mama, casado y a los treinta años de edad. Tu mama tiene miedo por que tu estas haciendo lo mismo—pero estás viajando sola, a los diecisiete años y en medio de una pandemia.” I understood what my dad tried to tell me, but somehow I still felt hollow inside, so hollow that I could feel my heart in the pit of my stomach. My parents were and are the reason I do everything I can do in my power—my desperation to make it out was not for me, but for them. So that crossing over, leaving their family behind, and starting a new life with twenty dollars in their pocket would not be in vain. I had developed enough anger and grit all these years so that we would not spend another holiday fearing the police, the possibility of la migra deporting my parents, or having my parents work on holidays to make the extra money. How could they not see that I was doing this for them?

As I reflect back, I think about how the roles of us immigrant families reverse over time. Our parents are superheroes to us, machines who never stop working hard—even through the most painful times. But as I am older, I see my parents as individuals I must protect from the government and the world. And although they may not have understood how good of an opportunity Cornell was for me, I had to pack my bags and move across the country on my own.

This is where my story begins. And although part of me hasn’t really reflected on all of it, or my journey thus far, I plan on telling it and writing it. If there is one thing I remember from my freshman year, it’s my English professor telling me, “Lots of people love reading, listening to songs, and watching movies. But it’s because everyone has a story to tell and if we love it, it’s because the writer was able to express something that we were not able to do ourselves yet resonate with.”

For many generations, those who migrate always migrate to places that provide better opportunities and a lifestyle than the one they had before. This is why my parents moved here almost thirty years ago, this is why I came here two years ago, it’s why thousands of people risk their lives everyday just so that they could get a taste of a better life. So let me ask you, if you were miles away from living the life you wanted, wouldn’t you take that chance?

Weaving: Spring 2021

Maiko Sein '23, Architecture

On January 31, 2021, my world, my family’s world, my community’s world was turned upside down. On January 31, 2021, there was a military coup in Myanmar. On January 31, 2021, like the generations before theirs, the youth of Myanmar took to the streets and protested for freedom, democracy, and peace. On January 31, 2021, like the generations before them, the military junta aimed weapons at them. On January 31, 2021, around the world, from NYC to Tokyo, the Burmese diaspora community, many of whom were displaced by the same military, took to their own streets and protested for freedom, democracy, and peace. For many it was familiar as they had done the same in their own youth. On January 31, 2021, the children of the Burmese diaspora community joined in on the fight for freedom, democracy, and peace for their parents’ country, for their grandparents’ country, for their friends’ country, for their country.

This was the start of the Burmese Spring Revolution.

The work is a plaid weaving titled Spring 2021. The warp, the up and down, are the protests, memorials, and fundraisers that my family and I attended throughout the NYC and Tri-State area. They are organized by the Burmese diaspora community in the area. The weft, the side to side, are the moments that spring that kept me stable. They are of my family, of home, of Zoom school. Together they interweave to tell the story of my Spring Revolution.

As a Burmese-American, I felt I was living two different realities that spring. The first reality as a newly turned 21 year old navigating the post-pandemic world, scared for the future but also scared for my friends and family in Myanmar. The other reality, I was more than myself. As I stood with the Burmese community at protests and memorials, I had never felt more strong and empowered. A year later, through this collage, am I able to decompartmentalize these two realities and see them as one.

Images from left to right:

- Memorial for murdered protesters at Jackson Heights, Queens, NY 03/13/2021

- Cousin’s college graduation streaming on TV, Brooklyn, NY 05/22/2021

- Protest in Times Square, NYC, NY 03/20/2021

- Pencil drawing for architecture class, Brooklyn, NY 03/22/2021

- Posters for the first protest against the military coup, Brooklyn, NY 02/02/2021

- Protest at Foley Square, NYC, NY 03/27/2021

- Protest at United Nations, NYC, NY 02/02/2021

- Birthday dinner, Brooklyn, NY 02/17/2021

- Twenty-first birthday, Brooklyn, NY 02/17/2021

- Merchandise to raise funds for Civil Disobedience Movement, Long Island, NY 05/08/2021

- Zoom class, Brooklyn, NY 05/11/2021

- Protest at Times Square, NYC, NY 04/03/2021

- Dad’s Burmese Spring Revolution bazaar sign, Manalapan Township, NJ 04/17/2021

- At the car dealership, last day with our family car of 10 years, Brooklyn, NY 05/15/2021

- Protest at Brooklyn Bridge, NYC, NY 03/27/2021

- Cherry blossom outing, NYC, NY 04/24/2021

- Seeing news on the TV about the military coup for the first time, Brooklyn, NY 01/31/2021

- Memorial for murdered protesters at Jackson Heights, Queens, NY 03/13/2021

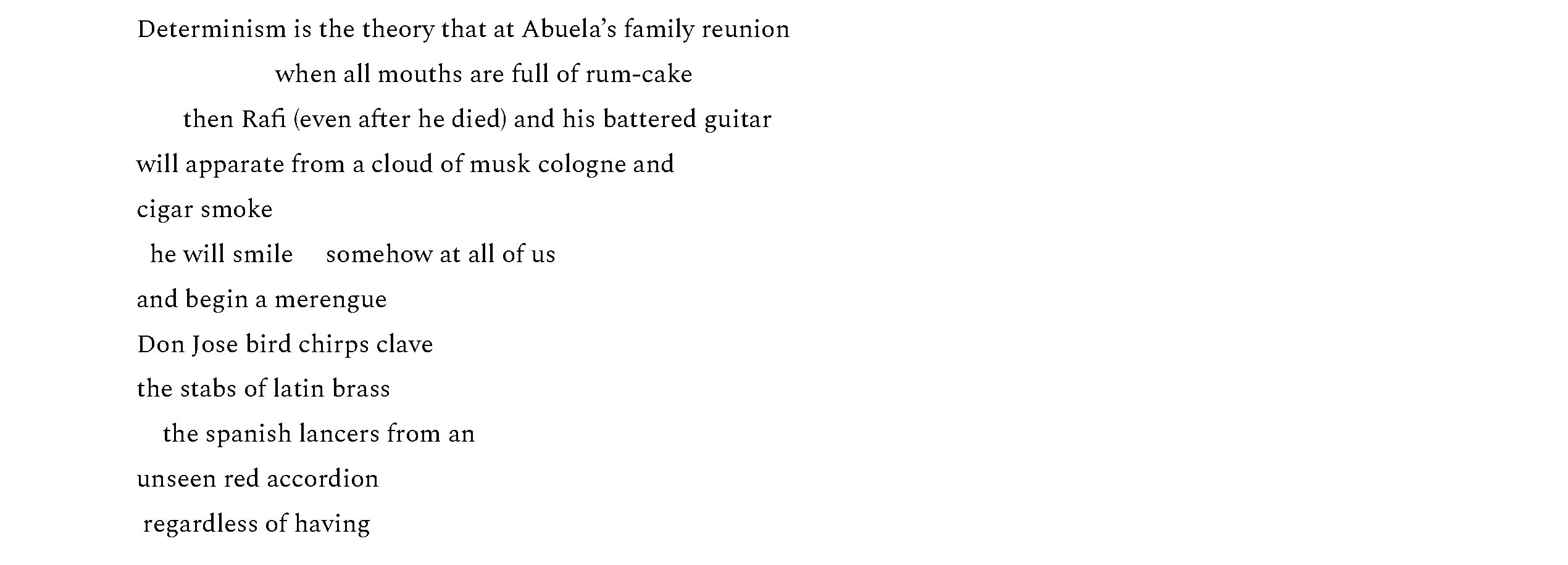

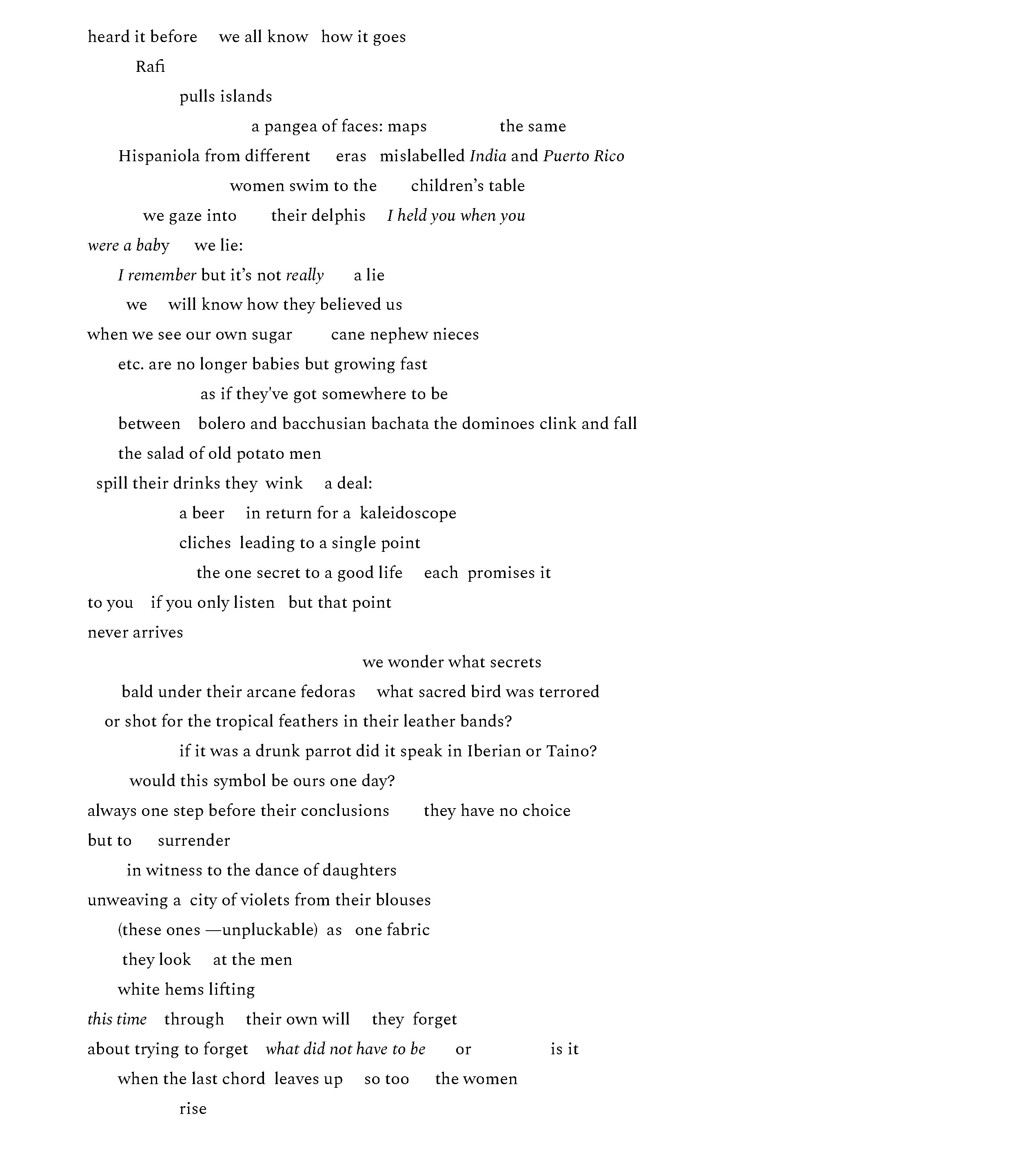

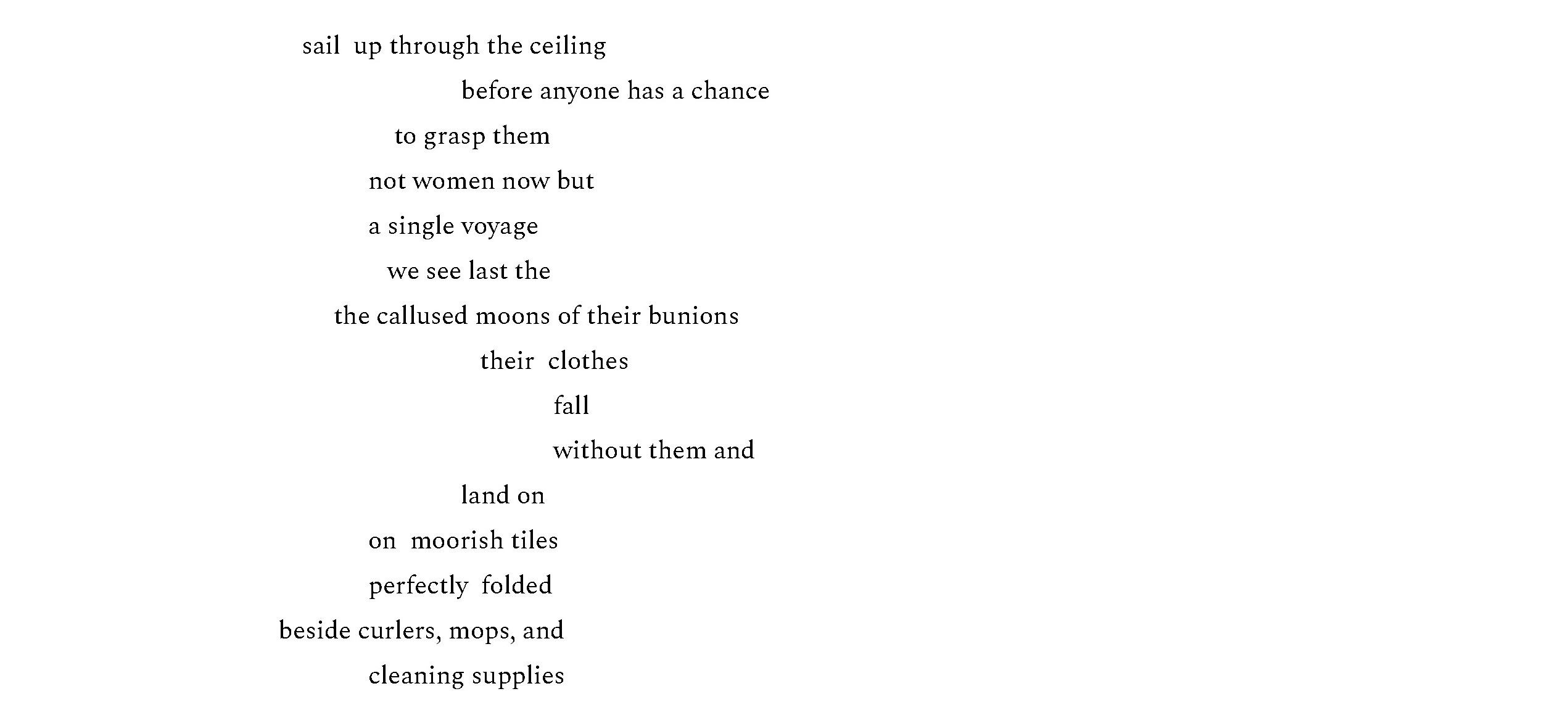

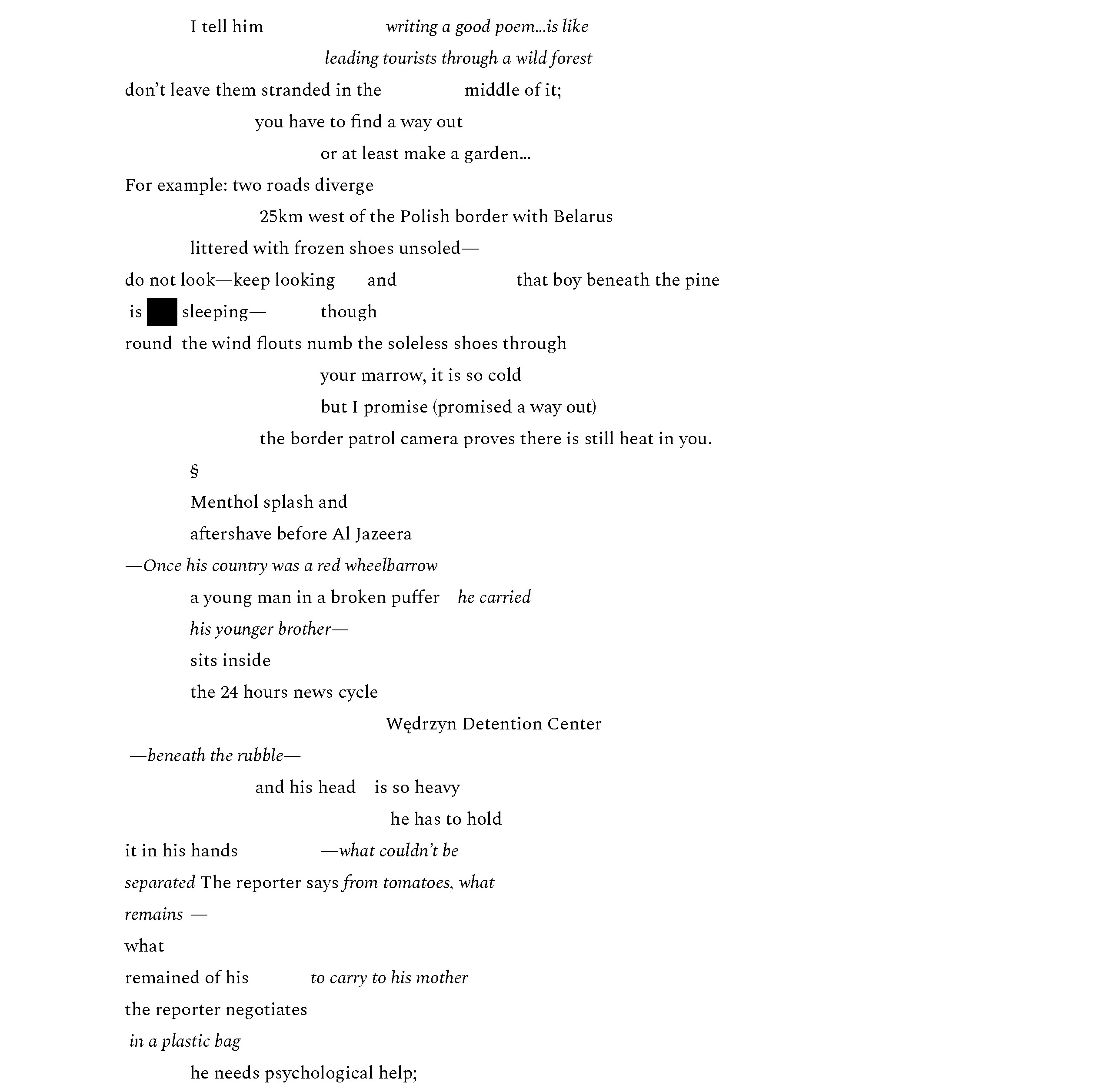

Who Knows the Arbitrariness of Being Born Some Place and its Magnitude

Juan Harmon, Graduate Student in Poetry

Once a Month My Father Brought KFC Home for the Family

-Written in Ithaca, NY; 2021