Historian of Water Studies the Movement of People

The Role of the Seas in Southeast Asia

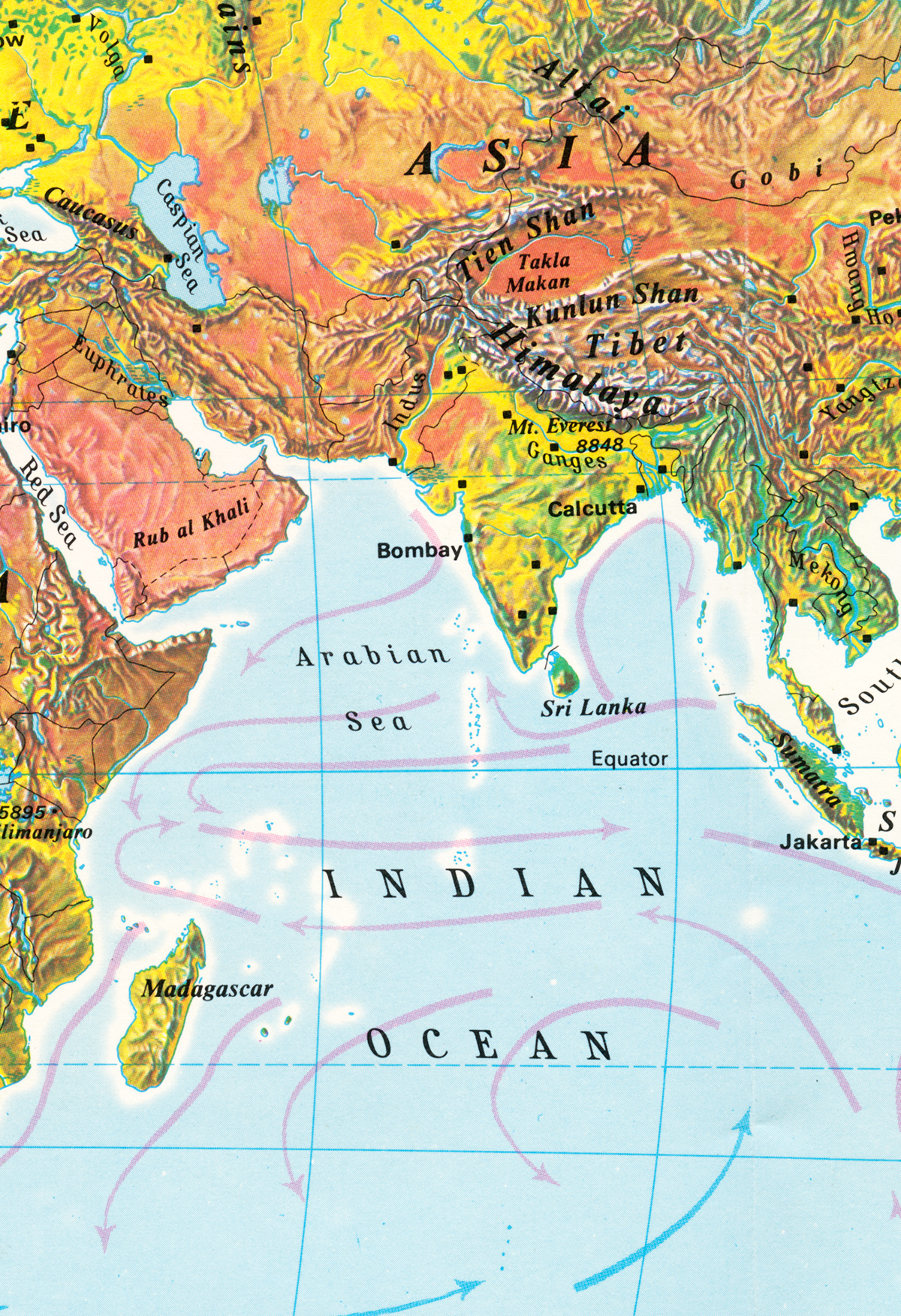

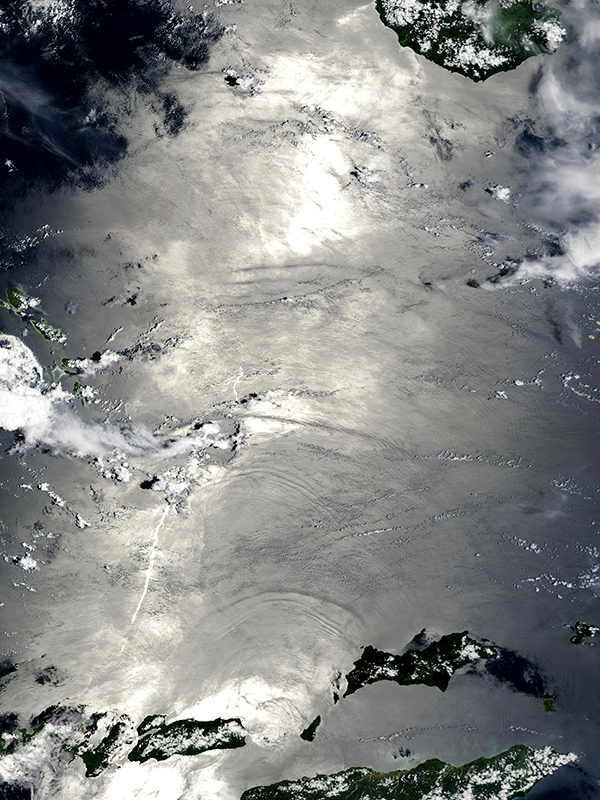

The seas play a significant role in life on Earth—this is as true today as it has been for millennia.

Eric Tagliacozzo knows this. As a professor of history at Cornell University, he studies Southeast Asia, one of the largest maritime arenas on the planet. He focuses on the movements of people, objects, and ideas throughout the region from the Colonial Age to contemporary times. Indonesia (the largest country in Southeast Asia) is also the world’s largest archipelago, Tagliacozzo explains, comprising some 17,000 islands. Connections forged across the seas here shaped Southeast Asia, but not always in ways that were foreseen, he says.

For example, the early great civilizations of the region built their prosperity on maritime trade, notably the selling of spices, which were readily produced throughout the eastern Indian Ocean and in demand outside the area. As colonization of the region by the British and Dutch increased, the trade arenas initially carved out along the coast by local merchants and local princes were absorbed by state actors as they established new political borders. Local people responded: to skirt the rules, avoid tariffs, and maximize their profits, traders began to smuggle commodities across boundaries—not just spices, but contraband that included opium, counterfeit currency, human beings, and more. The sea played a major part in the smugglers’ success.

“People across history have journeyed in many directions—sometimes simply to explore, other times to find better ways to live,” Tagliacozzo says.

He describes Bukit Cina (China Hill) in Malacca, Malaysia, to illustrate how “people wandered long distances—most often by traveling over the sea.” Bukit Cina is the location of one of the world’s largest Chinese cemeteries outside of China, with 12,000 graves, some of which date to the 15th century. There are accounts that the hillside had been first settled in the mid-1400s by a sultan of Malacca who married a Chinese woman. Historical records show that, by that time, Chinese had traveled to Malaysia for centuries, mainly for purposes of trade. (The distance from the Ming Dynasty capital in Nanjing to Malacca is more than 2,000 nautical miles.)

Unexpected Connections

“Waterways connect societies and geographies,” Tagliacozzo says. “By moving over water from place to place, people share commodities and knowledge. These connections shape local economies, cultures, and politics.”

In one of his research pursuits, Tagliacozzo studied the confluence of maritime travel and religion. He analyzed the significance of people making the Hajj (Muslim pilgrimage) from lands in the Indian Ocean to Mecca, beginning in the 13th century. They first traveled on sailing ships, and later (by the 19th century) on steamships. The pilgrimage aggregated many people from many different societies in the same place. As part of their experience, he explains, these religious wanderers—in some years half of the global total could come from Southeast Asia — prayed together, and they also traded goods such as carpets, brassware, gems, and spices. Their trade helped many pay for their voyages, and also helped begin the formation of important economic links, as well as religious ones, between Southeast Asia and Arabia. One result: Islam spread across Africa and Asia. Today, some 80 percent of Muslims are non-Arabic speakers, who live outside the Middle East.

“By moving over water from place to place, people share commodities and knowledge. These connections shape local economies, cultures, and politics.”

Another, perhaps more surprising result of this religious travel was the spread of cholera, Tagliacozzo says. The mass movement of people on Hajj became one of the main pathways for the disease, which moved from India to the Hejaz in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and then back with pilgrims on the transoceanic steamships to their home countries. The epidemic, which killed catastrophic numbers of people, spurred the European powers who controlled colonies in Southeast Asia to develop sanitary conventions to check the spread of infection.

Historical and Contemporary Perspectives

Maybe unsurprisingly, Tagliacozzo spends a good deal of time reading and discussing historical texts, as well as contemporary writings on Southeast Asia. (Among the Cornell courses he is teaching in 2019–20: The History of Exploration: Land, Sea, and Space—which he co-teaches with Steven Squyres, James A. Weeks Professor of Physical Sciences, who is known for his work as scientific principal investigator for the Mars Exploration Rover Project. Tagliacozzo also will teach Transnational Local: Southeast Asian History from the Eighteenth Century, and a first-year writing seminar called Global Islam.)

“Because my research shows the connections forged among peoples and cultures, one of the things that it addresses is the need for tolerance and equality.”

What methodologies empower researchers to study people on the move through geographical spaces and time periods such as these? Tagliacozzo’s research interests draw on numerous disciplines in addition to history—anthropology, geography, oceanography, epidemiology, ethnolinguistics, and more. He has helped assemble international networks of scholars, collaborators, and subject-matter experts on the ground in specific regions around the world. They serve as consultants and partners, providing information, varying perspectives, and leads on a wide variety of topics—including, for instance, the names of currency collectors who might be able to provide examples of old counterfeit currencies. When necessary (especially in areas of strife or armed conflict), these contacts also have served as guides who can vouch for him with local communities.

“Other times, I wander around and talk with chance acquaintances, such as people on the street, or sailors on the docks and ships,” he says. “I’m pretty okay with getting dirt under my fingernails. I want to understand some of the things they already know, living and working where they do. I’m interested in speaking with all types of people related to my topic, folks who are spread across socio-economic divides and geographical ranges of all sorts.”

“I’ve always been interested in how societies connect, and how people moved,” he says. “I’m fascinated with stories of how people end up where they do.”

Tagliacozzo credits this curiosity to his high school years in New York City, where he studied at the Bronx High School of Science with people whose backgrounds were from all over the planet. Then, as a graduating college senior, he received a Thomas Watson Fellowship in a national competition—he used the grant to travel the Indian Ocean and South China Sea to interview spice traders for a year. From then on, he was sold on seafaring.

“Because my research shows the connections forged among peoples and cultures, one of the things that it addresses is the need for tolerance and equality,” he says. “I’m not a fan of the thinking that is rooted in the concept of ‘the West and the rest’—that is not a useful paradigm for humanity.”

Tagliacozzo explains that his biggest challenge is often one of national boundaries.

“My work, by its very nature, has been transnational,” he says. “My research has moved across many of the borders and boundaries of time and space, just like the subjects I study—whether they are adventurers, spice traders, smugglers, religious pilgrims, or people migrating out of a desire for better lives.”

His purpose, Tagliacozzo says, has often been to humanize the movement of people, to tell the stories of their common humanity. “There’s a kind of sadness to history; it is often melancholic and quiet. But it also can force broad thinking—about others’ lives and about our own.”

by Jeri Wall for Global Cornell

Eric Tagliacozzo (PhD, Yale University) is a professor of history in Cornell University’s College of Arts and Sciences. He is the director of the Comparative Muslim Societies Program, as well as the Cornell Modern Indonesia Project, both part of the Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies. He also is a co-chair of the Migrations Taskforce.

He is one of two co-editors of the journal Indonesia. His most recent books include Secret Trades, Porous Borders: Smuggling and States Along a Southeast Asian Frontier: 1865–1915 (Yale University Press, 2005), and The Longest Journey: Southeast Asians and the Pilgrimage to Mecca (Oxford University Press, 2013)—and he is currently finishing work on In Asian Waters: Charting Maritime Histories of Asia. He is also the editor or co-editor of 10 other books in print, and he is one of four co-editors of the forthcoming Cambridge History of Global Migration, a huge, sprawling project that brings together many dozens of scholars to rewrite the history of modern migration on a planetary scale.